Letters from the past

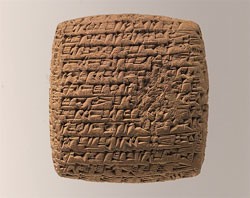

One fine day in the 20th century BCE Ilabrat-bani, an Assyrian merchant from Kültepe in Anatolia, wrote to one Amur-ili a letter concerning shipments of textiles, and providing advice for travel. The letter, written in cuneiform on a clay tablet, survived to reach present day historians and inform their research.

On June 8th of 1511 Piero Venier, a merchant living in Sicily, penned a letter to his sisters in Venice. It contained his observations from an Auto de Fe he’d witnessed in Palermo, where the Spanish Inquisition burned at the stake conversos suspected of heresy amid much public ceremony. The content of this letter also survived the centuries and enables historians to learn in great detail how the infamous persecutions of the Inquisition were conducted.

On January 8th of 1904 Orville Wright, of aviation fame, sent a letter to aviation journalist Carl Dienstbach in New York City, describing in detail the technical aspects of the first successful powered flight held in the preceding month at Kitty Hawk. The typewritten letter made it to the present day and its image can even be accessed online.

As these examples illustrate, historians can learn a great deal from the multitude of letters that constituted the personal correspondence of countless individuals ever since the invention of writing some five millennia ago. The original authors had no intention to benefit posterity; the letters were written for the recipients’ benefit only, yet they endured, and here we are. But this bountiful process for the transfer of knowledge down the ages is going to stop – right about now.

The digital drought

Five millennia of written record are about to grind to a halt. The fault, of course, is with our marvelous digital inventions: email, instant messaging, social media, and so on. So much better than a posted letter on paper, or papyrus, or parchment, or clay – as fast as an electric current or radio wave, cheap, reliable… but totally ephemeral. Clay tablets survive for millennia; paper can, absent major disaster, stay legible for many centuries. Email disappears, most of it as soon as you hit DELETE, but even the rest, the messages you archive in folders, will not survive for more than a decade or two: can you retrieve the mail you received in the 1980s? Can you even read the floppy disks you had back then, if they linger in the back of some drawer?

The thing to note is that we aren’t talking here about the “important” stuff, like congressional resolutions or presidential orders; someone is in charge of preserving those. The stuff we’ll lose is personal messages – the three examples above were messages between ordinary citizens. Email between us regular folks will not leave a permanent record for historians or archaeologists to peruse a century hence. The move to digital communications is creating a drought in the historical record. Where historians can deduce how people lived 100, 1000, even 3000 years ago by studying the wealth of letters they dig up (literally or figuratively), future historians will have nothing to tell them about our daily existence in the 21st century. Letters are the next best thing after a time machine – and when was the last time you actually wrote one on paper?

The same problem is happening with printed photographs. These ruled supreme for maybe 150 years, but now they went digital – and digital photos are just as ephemeral as emails in the long run.

And it isn’t just historians, either. Letters are also the stuff of personal memories and of family heritage. I know, because these days I’m working on the delightful if laborious task of sorting through a mass of hundreds and hundreds of letters, postcards, photos and documents left us by my late parents; these go back to the mid-19th century, and enlighten me about my family’s history over five generations; being a curator (among other things), I’m pulling together a family history book that can go to the next generations down the line. But my grandchildren will not have such an opportunity regarding anything beyond 1990. There will be no letters; no photos; no source material.

Double irony

This situation is ironic on two separate levels.

First, this loss of content is hitting us at a time when people can create content more easily than ever before. Never in history was authoring and communicating so easy, ubiquitous, and cheap. Between email, WhatsApp, blogging, YouTube, and so forth, people create content and send it around the planet in quantities unimaginable in times well within living memory. We publish more – and retain almost none of it for the future.

Second, one reason why we lose so much content is precisely because there is so much of it – because of the Information Overload we create. When sending a letter took some effort and expense, there were not that many of them. An average person could expect to write in a lifetime no more letters than would fit in a large suitcase; and the ones worth keeping would be easy to single out and keep in a box. The same with photographs: when you paid by the print, you would pick and choose, and fill a few albums to create a record of your life to leave to your descendants. Today, by contrast, everyone has thousands, tens of thousands even, of digital photos – too many to even sort through to pick the best ones. And as for email, we can barely cope with clearing our incoming load, much less curating it for posterity.

So what can you do about it?

Well, first, you must be aware of the problem. Most people aren’t; I remember this nice woman who proudly told me she was digitizing all the old photos her Kibbutz had from its founding days a century ago. I told her I sincerely hope she’s hanging on to the paper originals – and it took her by surprise when I explained that the digital versions will need expensive ongoing maintenance to keep them accessible as formats change over the years. Or that the CD-ROMs she was using had a limited lifetime, certainly much shorter than that of silver gelatin prints.

Then, when you realize the fact that your life is not only trickling away like sand, but is leaving a record that will disappear even before you do, you should think what you want to do about it. My advice? Think like a curator, as if you’re creating an exhibition of your life and times for your family and for your older self. (If you want to worry about future historians, go for creating time capsules – but that’s beyond my scope in this post.) It is said that a good curator is measured not by what they hang on the wall of an exhibition, but by what they leave out; this is especially true in the present context. Try to identify and retain the one message (or photo) in a hundred that the future deserves to see. Retain them both digitally and on paper – but remember to use quality paper and ink, and use a professional photo shop to create photographs, because what you print on your home printer will fade in a few years.

Your grandchildren will thank you!

Nathan, I seem to remember a science fiction story with a theme similar to your article. A group of explorers in a library of some distant civilization, where all records of that civilization had turned to dust, blown away and were lost forever.

I can’t recall the name of the story or the author.

Hey Boaz, I’m sad to say I don’t recall having read that story, though it would certainly make a great SciFi theme.

The story you are thinking of might be “By the Waters of Babylon” by Stephen Vincent Benet.

An (ephemeral) electronic version is at:

http://www.tkinter.smig.net/Outings/RosemountGhosts/Babylon.htm

Thanks Peter! Will give it a read.